“No!”

Porsche tosses the spark plug back towards the car.

He catches the next “hot chestnut” in his handkerchief. Raises the magnifying glass to it.

“No!”

Rudi fumbles to remove the eighth plug – as the Mercédès creaks & cools – as cars stream past the pits – as the rain continues to fall.

Was he losing the race?

The timekeepers were dead.

Who even knew what was happening any more?

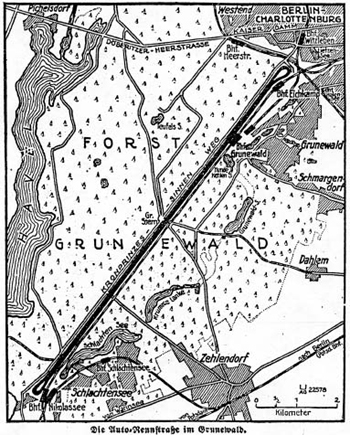

Sunday 11th of July, in a cool & breezy Berlin. An inauspicious Summer day for a new event. The 1926 Grosser Preis von Deutschland – the first international German Grand Prix – was a few hours away. Approaching the circuit – the AVUS speedway – crowds were jamming the roads. A quarter of a million people. Eager to see the curious mix of cars & drivers that the Automobil-club von Deutschland had rustled up. Eager for speed, daring, drama. Be careful what you wish for.

Twenty laps of a flat-out 12-mile speedway. Two long stretches of dual carriageway, topped & tailed by tight curves. 243 miles to decide the winner. The thirty-eight starters would leave the start line in their three classes, each class separated by two minutes.

1:25pm. The officials guide the competitors, in procession, to the start area.

2pm. In front of the rammed grandstands, the flag drops for the big cars. Class D, 2-3 litre ‘sportscars’ – blasting off the line and accelerating as hard as they dare. Chief amongst them the old-but-effective NAGs, the Austro-Daimlers, and Willy Cleer’s Alfa Romeo.

The next class forms-up, in a 3-2-3 grid at the start line. Class E, 1.5-2 litre ‘sportscars’. On the front row Breier (Bugatti), Rudolf Caracciola (Mercédès) and Komnick (Komnick) watch & wait. Watch the starter’s white flag held aloft. Watching… The Bugatti inches forward. Caracciola reacts, and jumps the start. The flag drops, just as Rudi checks himself… and the white Mercédès stalls.

The rest of Class E roars past. Adolf Rosenberger, accelerating hard from back row, chinks around the sister Mercédès… as Caracciola’s riding-mechanic, Eugen Salzer, jumps out to start pushing. The damn thing just won’t fire! Seconds pass. A minute passes. The small car class is about to move to the start line as, at last, the white car roars to life – sets off in pursuit of a race that is long out of sight.

Five miles, flat-out down the carriageway to the tight south curve. Five miles, flat-out on the opposite carriageway to the gently banked north curve. Across the line to complete lap 1. The timekeepers have the first times. Times passed to the painter, who will post them on the scoreboard at the north curve.

1: Rosenberger – Mercédès – Class E – 7:58.1

2: Minoia – OM – Class F – 8:14.3

3: Chassagne – Talbot – Class F – 8:22.4

4: Urban-Emmerich – Talbot – Class F – 8:38.4

5: Riecken – NAG – Class D – 8:43.2

6: Caracciola – Mercédès – Class E – 8:45.4

7: Berthold – NAG – Class D – 8:50.2

Those voiturettes are fast! But everything is in hand. Caracciola has already regained his lost minute against the big cars. Keep it neat, and trust in Dr Porsche’s “magic power”.

The first flying lap, and the OM’s Grand Prix pedigree starts to show. Minoia completes the lap in 7:17.3, an average of 100mph – it will be the fastest lap of the day. Rosenberger is right on the pace though. His Mercédès has a 15 second lead over Minoia, with Chassage’s Talbot a further 20 seconds back. Caracciola still hasn’t matched the pace of the 1.5-litre cars. A minute behind his teammate. Struggling to shake-off the start line drama?

Minoia continues to push hard into lap 3… and a tyre lets go. Sure to get your attention at 100 mph. Despite his remarkable pace, Minoia seems out of contention. He rejoins the race in 8thplace.

The two Talbots top the times and, following the OM’s pit-stop, are now 2nd & 3rd. Rosenberger still leads, by 35 seconds. Caracciola, building his pace, is now 4th – as the NAGs and Austro-Daimlers show signs of fading.

At the front, the pace continues to be relentless. The Talbots battling with Rosenberger’s Mercédès – Caracciola holding position – the NAGs suffering tyre failures.

Lap 6. Great drops of rain. Splattering on the crowds and track at the north of the circuit.

Spectators take whatever shelter they can find. The racers have little choice but continue – as drops turn to downpour – asphalt turns to “glass”. Still the leading four push on. The Talbots & Mercédès. Rosenberger – Urban-Emmerich – Chassagne – Caracciola. Rosenberger’s lead down to 48 seconds.

Flat-out in the rain, and Rosenberger is leaning out of his car. The Mercédès has a small tank of ether, to aid starting, and it is leaking into the cockpit. Down the return straight, “as slippery as soap”. The white car pulls out to pass an NSU at over 90 mph, as they approach the north curve.

Did Adolf’s head nod? A slow blink?

The Mercédès is already sliding as it enters the gently banked corner. Then Rosenberger gets on the gas too hard, too soon. Men & machine sail across the slick asphalt… to the grass slope. Launched – spun 360° – flipped sideways – flying towards the officials.

Airborne, they slice through the scaffolding structure of the scoreboard – sending the painter crashing to earth amongst the debris – and smash into the timekeepers’ hut. When the violence stops, the two student time keepers – Wilhelm Klose & Bruno Kleinsorge – are dead. Rosenberger and his mechanic Curt Coquelline are badly injured. The scoreboard painter – Gustav Rosenow – was rushed to hospital with crushed legs. He died, 12 hours after amputation.

…and the field races on.

The two Talbots now lead – Urban-Emmerich at the front, pushing hard. Caracciola in 3rdlosing some ground, as the remaining Mercédès goes a little woolly. Minoia parks-up the OM – talk of transmission trouble, but who who could blame him for walking away?

Lap 9, and the race is blown wide open. Coming out of the south turn, Chassagne’s steering breaks. The Talbot pitches off the road and overturns – ejecting the occupants and landing at the spectator fencing. Both men are taken to hospital – the mechanic, unconscious for 12 hours.

Moments later, under braking for the north turn, Urban-Emmerich’s Talbot snatches to the left. The AVUS surface is treacherous, and the leader shoots across the track – over the central reservation – across the opposite carriageway, just missing Caracciola. Still the Talbot slid, out of control – smashing through the fence and into the crowd, injuring a girl and a policeman. After repairs, Urban-Emmerich rejoins the race.

At almost the same time, a tie-rod on Mederer’s Pluto (a German-made Amilcar) shakes itself apart on the straight. The out-of-control machine leaves the road at full speed, and finds the race director’s Mercédès, parked in the centre of the circuit. The resulting crash punches the steering column into Mederer’s face, but the race director’s decision to show-off his car in the infield probably averted yet more loss of life.

This should leave Rudi Caracciola comfortably in the lead on his Mercédès. Instead, he’s pulling up to his pitbox. The old trouble, as Caracciola later explained:

“This car was known as ‘krummer Hund’ (‘crooked dog’) amongst us racing drivers. Everybody went carefully around, avoiding it, because until now the car had no sufficient staying power to last a long-distance race. The reason for this was not in the design. Doctor Porsche, who at that time was Technical Director at Daimler-Benz, had designed magic power into that engine. But at that time one was not as far advanced with materials as nowadays (1935), and when one extracted from the engine really all what it was able to deliver, it quickly became hot. Once it was really warm, it then began to ‘eat’ spark plugs by the dozen…..

In 1925 this car started only in short mountain climbs. But 1926 we had better plugs and with that we risked the Grand Prix of Germany.…later one cylinder started to misfire – nice present: to find from eight cylinders the one, which ‘pukes’. Nowadays, in a case like that, one throws out all eight plugs and installs a new set even when they are special plugs, where a set costs 200 Marks. 1926 we were not yet that smart.

I stopped at the depot, yanked the hood open and unscrewed every single plug, because at that time outside help of any kind was prohibited, and I threw the hot ‘chestnuts’ towards our dear Doctor Porsche who was standing in the pit and inspected with the magnifying glass every one of the plugs and threw them back to me. I think not till the seventh or even the eighth was the ‘Karnickel ‘(‘rabbit’) found – a stop of several minutes, a criminal, unpardonable luxury.”

‘RENNEN – SIEG – REKORDE’ : Rudolf Caracciola & Oskar Weller

Caracciola blasts back into the race. While the Mercédès has been sitting in the pits for eight minutes, the previously discounted Class D cars have found themselves at the front of race. Not just by circumstance, Riecken on the green NAG has just taken 50 seconds out of the rest of the field.

Lap 10, and again Riecken is 50 seconds faster than everyone – even Caracciola – and the race enters it’s second half with unexpected standings:

1: Deilmann – Austro-Daimler

2: Cleer – Alfa Romeo +2min 40sec

3: Clause – Bignan +3min 11sec

4: Riecken – NAG +3min 16sec

5: Caracciola – Mercédès +5min 10sec

The madness subsides – Caracciola finds the groove – starts reeling-in those ahead. Riecken is dispatched – Cleer only 13secs ahead on lap 12 – as Max Sailer leans from the Mercedes-Benz pit to gesture to Caracciola – “Faster! Go faster!”. On the white Mercédès, Caracciola & Salzer have no idea how the race is going for them – no clue as to their position or the standings.

Finally some luck for Rudi – Deilmann’s leading Austro-Daimler and the weather both break on lap 13. With a drying track Caracciola can deploy all of Porsche’s “magic power”… he doesn’t know it, but he’s hunting-down the leaders. Just doing what comes naturally – giving it hell.

Faster and faster – taking huge chunks of time out of those ahead.

Lap 13 – past Cleer’s Alfa. Next time around – past Clause’s Bignan, and a 25-second lead at the end of the lap. Riecken is still pressing-on on the NAG, but neither man knows how close they are. Each gives it their all to the end – across the line – 20 laps completed – to roars of approval from the enormous crowd.

Caracciola & Salzer on their ‘private’ Mercédès have won the first German Grand Prix – although they have no idea until they stop at their pits. A calm, professional drive – on a remarkable, confusing, awful day in motorsport history.

To the victors – 17,000 Marks and the AvD gold cup.

To Rudi – the title of Regenmeister (Rain-master), and a place in the heart of German motorsport fans.

To Mercedes-Benz – a new hero, to lead them into the future.

1: Caracciola – Mercédès 2hrs 54min 17secs

2: Riecken – NAG +3min 15sec

3: Cleer – Alfa Romeo +5min 59sec

4: Clause – Bignan +7min 49sec

Assembled from the (sometimes conflicting) research & writing of:

Caracciola / Weller, Etzrodt, Posthumus, Müller.

Thanks & respect to all.