County Down, Ireland: September 1916

Responding to deft touch, the Sopwith Strutter prescribes a shallow arc from Carnalea. Barely above the telegraph wires. No conscious check of bearing – instinctively the pilot dips a wing, and there… K and the children are at the homestead.

Waves, and kisses blown.

Banking right over Helen’s Bay. Swinging level. Bobbing on a cushion of air, over the Irish Sea.

Thirty-five year-old Leslie Porter – engineer, businessman, racing driver – is returning to France. This time, to war.

He would never see Ballywooly Farm again. Second time around reports of his death would prove accurate.

How different it had been in 1903. That year of revolution on the roads of Europe – when Irishmen first ventured into international motorsport, and vice versa.

Belfast, 1903

Willie Nixon – coming to, flat on his back in the road – barely had a moment to catch his breath before the hubbub surrounded him.

“You all right, son?”

“I didn’t see you. I’m so terribly sorry.”

“Lift his bicycle before something happens to it.”

Willie sat upright as a sea of faces in the half-light vibrated in his vision. ‘The ticket!’

Dragging his coat back over his shoulders he rummaged through pockets, breathless.

“Will you be fine to get home, son?”

There it is, ‘Belfast to Birmingham, single’.

“Aye, I’m grand… Everything’s grand.”

The craic was good in work – at Johnston’s Saddlery. The guys in the cycling club laughed at the joke too. “No need for a return ticket. If we win they’ll carry us home – and sure if it all goes wrong, I’ll be carried home just the same.”

The Mother didn’t find it amusing. Unsettling – there was concern for this new adventure, and for Willie’s weak heart. But sure, hadn’t the cycling worked out fine… and the motorcycle racing? And what can ye do – the boy has to find his own way.

A motor car with a racing pedigree. A genuine race-proven machine, converted into a tourer. Perhaps with a small brass plaque on the dashboard, to get the message across? What a thing it would be. Sure to impress the chaps at the club.

This was the not altogether original idea presented to Mr C.E. Allan of Stormont Castle, Belfast – managing director of Workman, Clark & Co. Ltd., shipbuilders. The car he was offered was a 50hp Wolseley, a machine set to be blooded at the Paris-Madrid road race.

The Paris-Madrid race of May 1903 was planned by the Automobile Club de France to be the culmination of the first decade of motor racing. A three-day dash between the two capitals: Versailles to Bordeaux – Bordeaux to Vittoria – Vittoria to Madrid. 784 miles of unmade roads. Hanging on to a twisting & bucking machine – at 80 miles-per-hour.

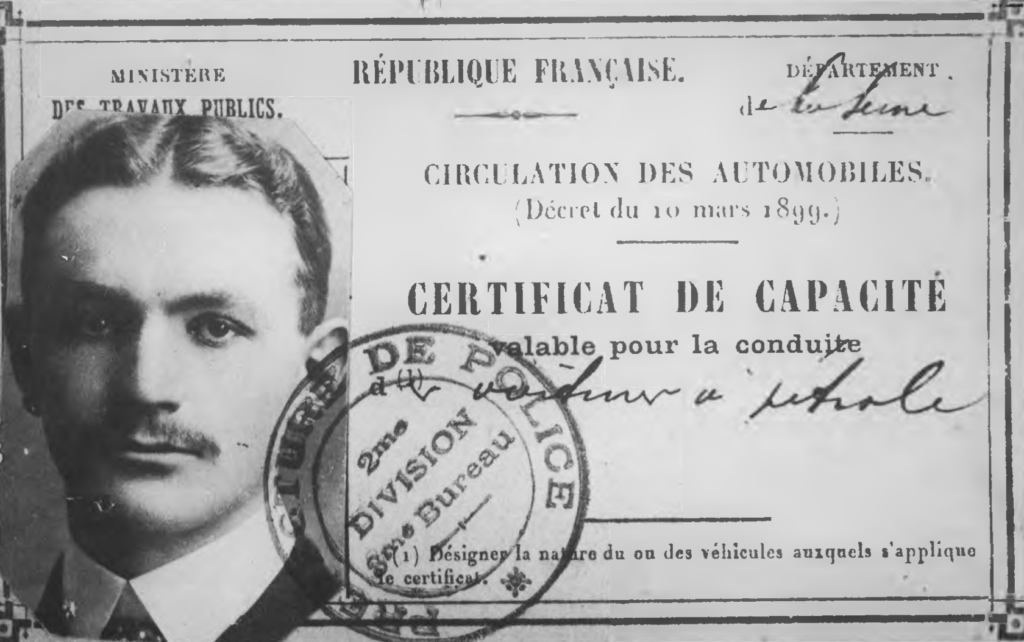

Allan duly placed his Wolseley order with The Northern Motor Company of 5 Montgomery Street, Belfast, on condition that he would take ownership of the rebuilt machine after the great race. The Northern Motor Company – the first motor car dealer in Ireland – was lead by twenty-two year-old Derry man, Leslie Porter

It was Porter himself who accepted the task – indeed had contrived the whole thing. He would oversee the completion of the racing car at the Wolseley works at Birmingham, take the machine to Paris, and drive it in the great race.

What an adventure, especially as his cycling & motorcycling friend & rival Willie Nixon was coming along as riding mechanic. Sure it’ll be great craic!

The Wolseley entry was to be three cars, plus a reserve, in a team lead by the car’s designer Herbert Austin. Leslie Porter arrived in Birmingham on 4 May to oversee the detail and testing of his car – electing to add an additional flap to cool the radiator tank. Austin’s car, prophetically, was the only Wolseley fitted with wire braces on the wooden road wheels. Willie Nixon arrived – on his one-way ticket – on 15 May and the team set forth for Paris, and the race start at 3.30am, 24 May.

The Porter/Nixon Wolseley was singing on the run to Newhaven – a fine machine. Off the steamer at Dieppe and once a little local difficulty was settled – detention by the police and a 25F fine for hitting a dog – the Belfast lads gave the Wolseley its head again, and averaged 60 mph for the run to Paris. Things were looking very promising, even if the Wolseley needed the rear axle knocked back into shape after hitting an open drain at sixty.

The first day of this epic race was over familiar, storied roads. Paris to Bordeaux was, and remains, iconic for both motorists and cyclists. Moreover, a pre-dawn racing start from Versailles – thousands of spectators on foot & vélo, with paper lanterns – is the perfect, romantic vision of pioneer motor racing. Motor sport in La Belle Époque was a paradox – modernity and horror mixed with politesse and society correctness – yet, the escape from Paris under cover of darkness is so elemental that it would be reprised by Thierry Sabine in his first Paris-Dakar of 1978.

Charles Jarrott – number 1, first away from the start – wrote in 1906 of that morning of 24 May 1903:

What do I remember of that race?

Long avenues of trees, top-heavy with foliage, and gaunt in their very nakedness of trunk; a long never-ending white ribbon, stretching away to the horizon; the holding of a bullet directed to that spot on the sky-line where earth and heaven met; the fleeting glimpses of towns and dense masses of people – mad people, insane and reckless, holding themselves in front of the bullet to be ploughed and cut and maimed to extinction, evading the inevitable at the least moment in frantic haste; overpowering relief, as each mass was passed and each chance of catastrophe escaped; and beyond all, a horrible feeling of being hunted. Hundreds of cars behind, of all sizes and powers, and all of them at my heels, travelling over the same road, perhaps faster than I, and all striving to overtake me, pour dust over me, and leave me behind as they sped on to the distant goal of Bordeaux.

…I have sympathy now with the hunted animal, for once in my life I was hunted.

‘Ten Years of Motors and Motor Racing 1896-1906’, Charles Jarrott

The pesage weigh-in taken care of, and given the race number 243, the Porter/Nixon machine was given a final check. Now the nervous wait for the start time – two hours of watching rivals race off into the dawn.

The time was passed with an old friend from Belfast. Frank Fenton, who the lads knew from their sporting circles, was now a director of Clément-Gladiator in Paris. At Versailles as a commissaire for the great race, he was at the start to wish them well as they took their place on the line. But there was one last, private matter to deal with. Leslie took Willie aside.

“Here, take this. Stuff it inside your jacket.” “What?” “It’s the rest of the money, 7000 Francs. If we run into trouble I’m more exposed. If it happens, it should be enough to send me home.”

5.32 am. Porter & Nixon join the hunt.

The first miles are frantic, and fast. Ahead on the road, the other Wolseleys are suffering with overheating bearings – dropping back. Not the 243 of Porter & Nixon. Earlier starters are dispatched by the Belfast lads one at a time, on the road to the first control at Chartres. Yet the dangers are becoming apparent.

Twenty-five miles in and a spectator’s car reverses into their path. Leslie keeps his foot in, aims for the narrowing gap, and they are through with a clash of wheels. Soon after, cyclists in the road. A tug on the steering wheel changes the Wolseley’s trajectory, but it’s heart-stopping stuff – dancing over the road surface at sixty-plus miles-per-hour.

Yet they are flying, nerveless, passing car after car.

Improbably, the Wolseley finds itself dicing with the works Mercédès 60 of Terry, which had a much earlier start time. Side-by-side at full speed, neither man giving an inch.

It happened in a blink.

As the road eases left, Terry is pinched on the inside. The front left wheel of the Mercédès clouts the pavement, hard. The Continental racing tyre bursts – machine & men leap & buck across the road – the bare rim digs into the road. Porter brakes as hard as he dares, as the Mercédès’ petrol tank bursts – the Wolseley shoots through the wall of flame that fills the roads – and slides to a halt.

90 HP WERNER CAR REAR AXLE BROKEN – TERRY 60 HP BURNT – ALL OTHER 90 HP MISERABLE IN RACE – BRAUN GASTAUD WARDEN WELL PLACED IN BORDEAUX

Telegram: To DMG, Cannstatt from Emil Jellinek, Paris – 24 May 1903

It was a miracle that everyone walked away from the accident – no injuries. Yet along the route there were rumours, and stories, and reports. The day was young, but the race was not going well. Some said carnage. Authority was talking note.

The Wolseley was not in good shape as Leslie & Willie tried to restart – overheated bearings it appeared, like their teammates – so they limped to the control at Chartres, one of the last to arrive. Passed by many on the road – all their good work undone.

An official’s car stops at the gate house, beside the level crossing. The flag marshal runs across to receive his instruction. That’s it now – most of them are through – go get some food. A long day for the flagman at the village of Bonneval.

Chartres provided a moment to breathe, and for the Wolseley to cool. Replenished – ready to run again. Waiting for the signal, almost last to leave control – spectators pushing into the road. Porter high on the driver’s seat, on the right of the car. Nixon low to the floor, on the left, feet pressed against the dashboard.

“If the people keep crowding over the road like this there will surely be someone killed.”

“Aye, Willie. You’re not wrong.”

With that, they were gone. Out of town and onto the long, straight road – twenty miles, flat-out to Bonneval.

The machine gorged itself on the soft, dust-filled air. The steady baritone note of the engine. The thrum & chirp of tyres skipping on the loose road surface. The rush, the speed. Tranquility in motion.

‘…the holding of a bullet directed to that spot on the sky-line where earth and heaven met.’

In the distance, through the dust, Leslie could see that the road must turn. Straining to ascertain the corner – holding the Wolseley at flat chat. There is neither time nor speed to waste, if they are to get back in contention.

Left-hand turn – no blue warning flag – easy left.

Lift – scrub the speed down to 60 mph – turn in.

Porter grabs another fistful of lock – what is this unmarked bend? The Wolseley understeers – slews across the road – front-right wheel groaning under the pressure. The corner continues to tighten, to a railway crossing, but the route is no longer their concern. Out of control, with no way to arrest their speed, the Wolseley is heading straight towards the gatekeeper’s cottage.

Porter swings the steering hard right. Tyres bite, wheels split under the pressure. The machine rotates, lurches right – crashes through the hedge, into the field beside the cottage. The front of the Wolseley is clear, then – wheels fold, the engine grounds, and the Wolseley is dashed sideways into the cottage wall.

A scene of horror. Both men cast from the machine, unconscious, as it spews a river of fire towards the cottage. A torn steering wheel – a watch, broken yet still counting race time… a bundle of French bank notes, smouldering.

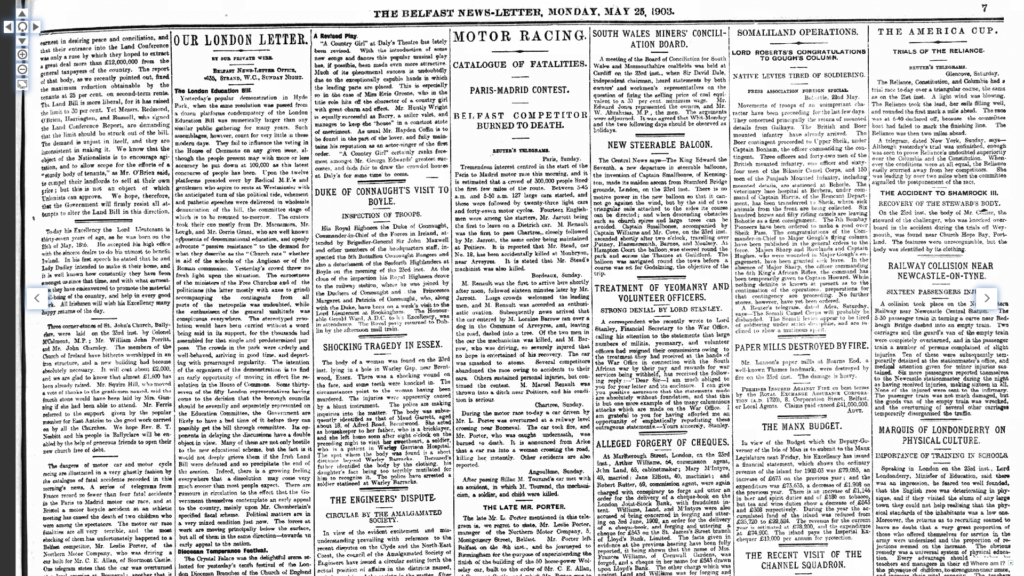

MOTOR RACING.

CATALOGUE OF FATALITIES.

PARIS-MADRID CONTEST.

BELFAST COMPETITOR BURNED TO DEATH.

Reuter’s Telegrams

Chartres, Sunday

During the motor race to-day a car driven by Mr. L. Porter was overturned at a railway level crossing Bonneval. The car took fire, and Mr. Porter, who was caught underneath, was burned to death.

The Belfast News-Letter – 25 May 1903

Leslie Porter – coming to, flat on his back in the field – barely had a moment to catch his breath before the hubbub surrounded him.

“Willie! Where’s Willie?”

It was hopeless. Sitting low on the left of the Wolseley, Willie Nixon had struck the cottage wall when he was thrown from the machine. He had died instantly. Leslie could only look on as others fought to save his body from the raging fire.

Too late to correct the appalling error in the Belfast newspapers, Leslie Porter sent a telegram home:

TYRES COLLAPSED AT CORNER FROM WHICH FLAGS HAD BEEN REMOVED JUST BEFORE OUR ARRIVAL. NIXON KILLED INSTANTANEOUSLY AGAINST WALL, ALSO BADLY BURNED. UNINJURED. LESLIE PORTER.

The Paris-Madrid race had left a trail of death & destruction on the road to Bordeaux, and there it was halted by the authorities. Spain made it known that the race was no longer welcome, and so a result was called and the competitors’ machines were towed in shame to the railway station, by horses. The press, relishing the drama, dubbed it ‘The Race to Death’ – the future of motor sport was uncertain. All eyes now turned to the Gordon Bennett, planned for 2 July in Ireland.

RACE SPAIN PROHIBITED – WERE NOT ALLOWED TO TAKE CARS FROM PARKING AT SIX EVENING – WILL TOMORROW IF POSSIBLE RETURN ALL MERCEDES IN COLUMN – WILL ACCOMPANY GASTAUD OR BRAUN AND MAKE A FUSS – CHARLEY

PARK UNDER MILITARY GUARD – SHALL GET CARS ONLY UNDER CONDITION TO RETURN THEM BY TRAIN – ALL MANUFACTURERS GAVE IN BECAUSE EVERY RESISTANCE USELESS – SPOKE WITHOUT SUCCESS TO PREFECT – CHARLEY

Telegrams from Karl Lehmann ‘C.L. Charley’, Bordeaux to Emil Jellinek, Paris

William John Nixon – 27 years-old, from Cavehill Road, Belfast – was laid to rest in Cimetière St Sauveur, Bonneval, at noon on 28 May 1903. Frank Fenton, the old friend from Belfast, made the necessary arrangements through his Paris lawyer. Together with Leslie Porter he found an English-speaking Protestant clergyman to conduct the service, and made arrangements for Willie’s brother and cousin to attend. They noted that the people & Mayor of Bonneval were “very kind and sympathetic”. There were wreaths from the Mayor of Bonneval, Wolseley, Leslie Porter, and friends in Belfast. The following day an enquiry was held, then everyone made their way home.

In 1909 Charles Jarrott commissioned a fine memorial at Willie’s grave, and had an iron cross placed at the gatekeeper’s cottage.

Willie Nixon and Leslie Porter are rarely mentioned these days, but they are honoured. Honoured by a century of Irishmen who followed in their brave, first footsteps. Honoured by our Grand Prix winners. Honoured by William Creighton & Liam Regan, setting off from Belfast to dance a rally car across dusty continental roads. The machines change often, the men remain the same.

The unknown presents itself at every yard, and your neck and the safety of your car depends on the soundness of your judgement. Are you better in dealing with these ever-recurring problems of driving than the man immediately in front of you, or the man just behind you? If not, he gains and you lose; you drop farther back and are passed from the rear, and as you wrestle mentally and physically with all the difficulties of the trial the excitement of it enters into your soul, and you realise that this is a sport of the gods.

‘Ten Years of Motors and Motor Racing 1896-1906’, Charles Jarrott

Fienvilliers, France: 22 October 1916

Responding to deft touch, the three Sopwith Strutters prescribe a shallow arc and land at the field. Flight leader Captain Leslie Porter is unimpressed. On operational patrol behind enemy lines his men had become confused with a second flight ordered to carry out the same patrol, at the same time. What was Dowding thinking? Porter had made the decision, after an hour in the air – bring his men home, refuel, go again. Now on the ground there was intransigence. No, they were not to refuel. They had their orders. Take to the air immediately.

Leslie Porter lead his men to the front, and was never seen again. After months of enquiry by the Porter family at the highest levels of European aristocracy, the German authorities returned Leslie’s silver locket.

In a city all ready filled with grief, Leslie Porter’s passing caused great sorrow.

The press called him ‘The Man Who Died Twice’.