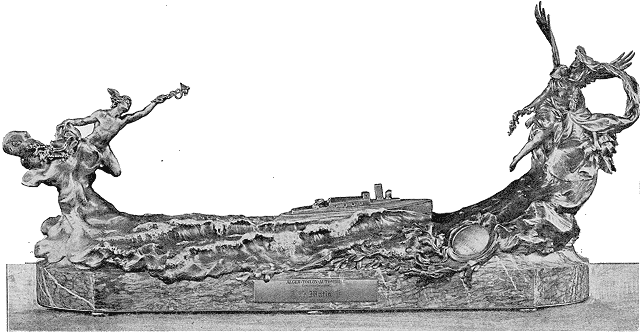

“I have in my garden a bronze statue the patina of which has the soft shade of light emerald and which readily catches the eye of the passer-by… The pedestal of the trophy has in embossed letters two inscriptions. The front one is a little compromising:

ALGIERS-TOULON RACE FOR MOTOR BOATS – ORGANISED BY LE MATIN IN 1905 – PRESENTED BY THE WAR MINISTER BERTEAUX.

The second inscription on the back is, however, cruelly mocking:

ENERGY CONQUERS THE ELEMENTS”.

Guy Jellinek-Mercédès – ‘My Father Mr Mercédès’, 1961

It’s interesting, if not unsurprising, news that the Mercedes-Benz Grand Prix team is aligning with INEOS Britannia to develop the British challenger for the America’s Cup. INEOS, of course, being the common element in both organisations. It did however make me think of other Mercedes racing adventures on the waves… after all, the Mercedes star has three points for good reason!

The America’s Cup was all ready fifty years-old when the brand-new Mercédès engine won it’s class in the Nice international regatta. Motorboat racing was new & cutting-edge, and Emil Jellinek-Mercédès and his Paris-based Mercédès distributor Karl Lehmann – “Charley” – were at the heart of it. It was Charley who, at dinner during the 1904 motorboat races at Lucerne, brought up the idea of a trans-Atlantic race. The great & the good around the table riffed on it – how the logistics would work – how the fuel could be managed. After all what’s a boat race to men who simultaneously organised challenges for the Gordon Bennett and the Paris-Madrid road races?! But in the cold, sober light of day they ‘trimmed their sails’.

Charley founded the ‘Coupe de la Méditerranée’, got ‘Le Matin’ involved, and provided 10,000F – a figure matched by Camille Blanc of the International Sporting Club. Jellinek, slightly begrudgingly, agreed to be involved. The race was not to be across the Atlantic, but rather from Algiers to Toulon – in two stages, at the start of May 1905. There was a buzz of interest and entries, and soon a start list of seven was confirmed. Each competing motorboat to be accompanied by a French navy torpedo boat.

- ‘Malgré Tout’ – Ch. Roche

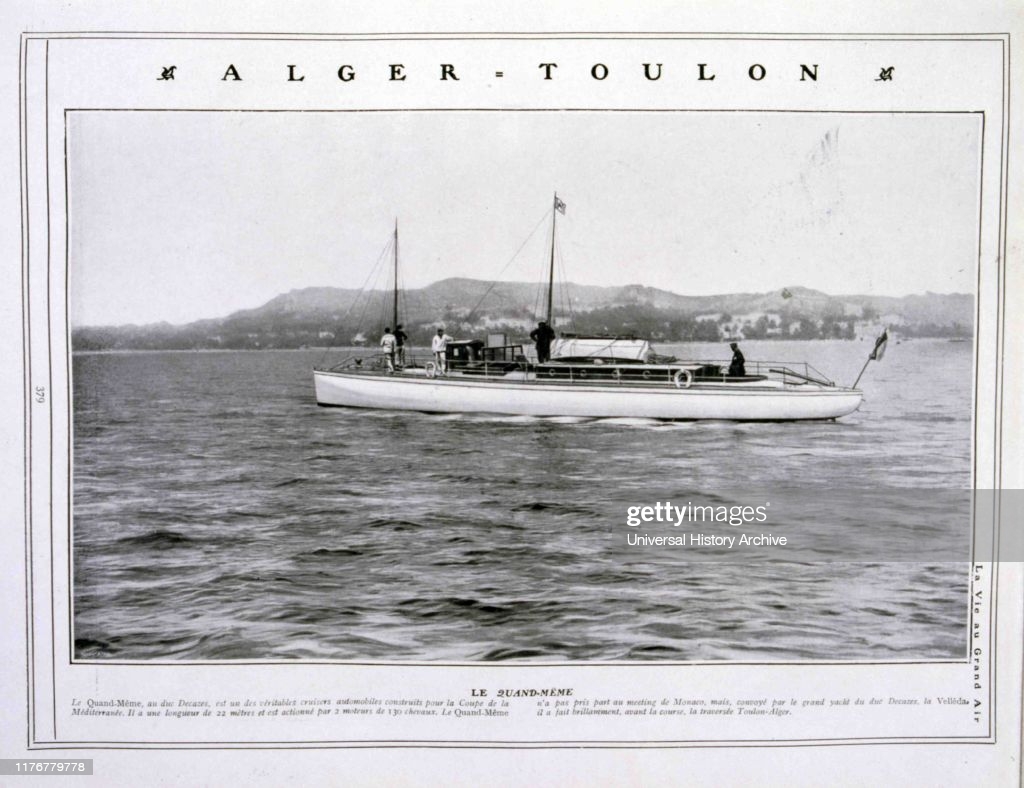

- ‘Quand-Même’ – Duke of Decazes

- ‘Mercedes-Mercedes’ – E. Jellinek-Mercédès

- ‘Mercedes C.P.’ – C.L. Charley-Pitre

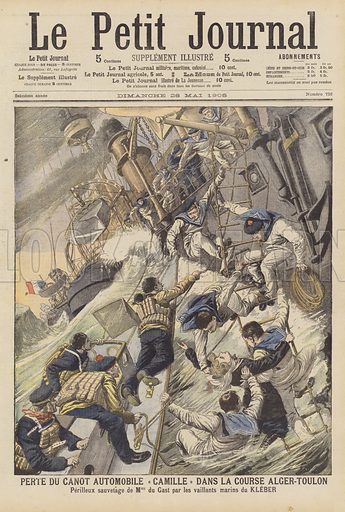

- ‘Camille’ – Mme C. du Gast

- ‘Heracles II’ – Heracles Company

- ‘Fiat X’ – FIAT, Turin

Competitors and support boats slowly made their way to Algiers to await the start… then the good weather broke. After two days in port the east wind dropped a little, and the decision was made to race.

“We left Algiers in good weather and with a light wind blowing from the north-west. The escorting ships and the racing yachts in this beautiful bay were a glorious sight, with the terraced town rising as a background to complete this splendid picture”

Paul Chauchard – log book of ‘Quand-Même’

Autoboats In Long Race

Seven Leave Algiers For Toulon — Warships Acting As EscortsALGIERS, May 7—Seven autoboats started at 6 A. M. in the long-distance race from this port to Toulon. Lewis Nixon’s Gregory, which was to represent the United States in the contest, was not present.

Every precaution has been taken to prevent mishap, two cruisers and seven torpedo-boat destroyers accompanying the races. The sea was somewhat choppy, which interfered with the progress of the boats. A mail steamer which arrived here this afternoon reports passing the boats, two of which were being towed. Their arrival at Port Mahon is expected to-morrow.

New York Times – 8 May 1905

In Toulon a regatta and festival kept the people entertained, as they looked to the horizon. What happened next is perhaps best told by this period report.

The Algiers-Toulon Motor Boat Race

Scientific American – 3 June 1905

by the Paris Correspondent of the Scientific American

The Algiers-Toulon race was organized in the first place by the Matin, one of the leading Paris journals. Then followed the cup offered by M. Charley, the Paris representative of the Mercedes automobile company. The French Minister of the Marine offered a prize, and also lent his aid to the event, and allotted a torpedo destroyer to accompany each of the racers. This encouraged the constructors to build a type of especially heavy racing boat, adapted to run in the open sea. The racers varied from 30 to 80 feet in length, and the motor ranged from 35 to 200 horse-power. The smallest boat was the Italian racer Fiat, which measured 30 feet in length, while the largest, the Quand-Meme, owned by the Duc Decazes, was 74.46 feet long, 9.81 foot-beam and 1.05-foot draft, and fitted with two motors of 100 horse-power. The Camille, a Paris-built racer of 60 horse-power and 43 feet length, was piloted by Madame du Gast, the well-known sportswoman. The Heracles II was built of mahogany. it had a double hull, with tarred paper between the layers. The machinery was well protected by a liberal deck. The boat was 35 feet long, had a 60-horse-power motor, and carried a crew of seven. The hulls of the two Mercedes boats, besides those of the Camille and Heracles II, were built by the Pitre Company in paris. The Mercedes C. P. had a 45-foot steel hull and a 90-horse-power Mercedes motor. She carried a crew of six. The Mercedes-Mercedes was 60 feet long, and had 2 90-horse-power Mercedes motors placed in line, one behind the other, and driving a single propeller. This boat was provided with a mast and smokestack and carried a crew of five. The Malgre Tout was 65 feet long, 11 feet beam, and had a 6-foot draft. Its weight was 14 1/2 tons, 5 tons of which was due to a heavy cast-iron keel. It was rigged as a yawl, and carried 170 square yards of canvas. Both the 120-horse-power motor and the boat itself were built by M. Roche. The crew consisted of six men. The Quand-Meme, as can be seen from the illustration, was the largest and handsomest boat of the lot. It weighed 15 tons, and had a draft of 4 feet. Two Beaudoin motors of 100 horse-power each drove twin screws. This boat had nine men on board. Despite the fact that she carried 700 gallons of gasoline, lack of fuel was one of the causes of her final abandonment.

The start took place from the port of Algiers at 6 o’clock in the morning, led off by the Quand-Meme. Then, at intervals of a few minutes, came the Mercedes C. P., the Mercedes-Mercedes, the Fiat, the Camille, the Malgre Tout, and the Heracles II. The time was taken upon one of the large torpedo destroyers, which lay at the mouth of the port, as the boats passed by at full speed. The line of boats was preceded by La Hire and followed by the Mousquelon, while the battleships Kleber and Desaix accompanied the fleet on the passage. A few of the motor boats, such as the Heracles II and the Malgre Tout, hoisted their sails at the start, while the rest ran with the motor alone. They soon disappeared in the distance. Six of the boats succeeded in arriving at Mahon in good order. First came the Fiat at 6:15 P.M.. it having made the 195 nautical miles (224.79 statute miles) from Algiers to Mahon in a little over 12 hours, with an average speed of 16 knots (18.54 statute miles) an hour. Then followed the Camille at 10 o’clock, taking 16 hours for the trip. Not long after came the Mercedes C. P. at 10:43 (17 hours), then the Mercedes-Mercedes at 12:30 (18 1/2 hours), and the Quand-Meme at 1:45 A.M. (20 hours). The Malgre Tout came into port towed by the Carabine, while the Heracles II did not arrive until late in the morning, at 11 o’clock.

Thus the valiant little Italian boat, the Fiat carried off the honors of the first part of the course. It came into port accompanied by the destroyer Arc, and after the latter had anchored, the Fiat made a brilliant run across the port at full speed, amid wild cheering from the assembled crowd. it had made the long trip of over 200 miles without the slightest accident, and had kept up a very regular speed. Preparations were then made for leaving Mahon, and continuing the second part of the race to Toulon. But on account of the bad weather and the heavy sea which prevailed, they were obliged to remain in the port for several days, and could not start again before May 13.

The boats started at 4 A.M. in good order, but afterward the sea became rougher. The Fiat had to be taken on board La Hire when 45 miles out from Mahon, as it passed through the smaller waves and shipped water. Then some of the other boats were taken in tow, owing to different accidents. These were the Mercedes C. P., the Heracles II, the Malgre Tout, and later on, the Mercedes-Mercedes. At 10 o’clock the breeze stiffened, but the Camille was making good headway, as was also the Quand-Meme. At 5 P.M. the Camille had to be taken in tow. The weather had been comparatively good at the start, but toward 10 A.M., the barometer fell very fast, and toward evening a violent storm came on, which was one of the worst ever seen in that region. Under these conditions most of the boats were taken in tow, and afterward abandoned, as they could not be hoisted into the destroyers in such a heavy sea. The Mercedes C. P., which had been running admirably, was later towed by the Hallebarde, but the boat was swamped in the heavy sea and the towline had to be cut. The Camille, also under tow, broke away and was left at the mercy of the waves. It was only with great difficulty that the battleship Kleber was able to save Madame du Gast and the crew. The Malgre Tout, Heracles II, and the Mercedes-Mercedes met with a similar fate, while the Quand-Meme was kept afloat until 5 P.M. on the 14th, when her crew were obliged to abandon her and be taken aboard the Arbalete. Thus all the boats were lost with the exception of the Fiat. Had it not been for the exceptionally heavy tempest, there is no doubt that they would have reached Toulon.

In the end the blame was apportioned, rightly or wrongly, to ‘Le Matin’, which had the job of providing weather reports for the event. Prizegiving was… ‘fudged’. Awards were divided between the six wrecks in the order they were lost. Therefore first prize went to ‘Camille’, second to ‘Mercedes C.P.’, third to ‘Mercedes-Mercedes’, fourth to ‘Quand-Même’, fifth to ‘Heracles II’, and sixth to ‘Malgré Tout’. ‘Fiat X’ got a consolation prize, for surviving – having been pulled aboard her escort ship.

All told, the race was a disaster – but it appears that Jellinek remained sanguine about his loss. Perhaps he was just too busy to think about it? After all he had his hands full; chasing improvements in the Mercédès cars, dealing with customer complaints, urging DMC to invest in racing, preparing for the Gordon Bennett trials & race, etc.. For Emil Jellinek-Mercédès there was always another challenge, another opportunity to ‘do better’.

“My father was not resentful. For a sunken yacht and much lost money he was handed a fair weight in bronze which glorified victory and confirmed defeat forever… He gave the heavy prize a place before the bow window in the Villa Mercedes and for forty-two years the figure has clenched her fist towards the capricious sea.”

Guy Jellinek-Mercédès – ‘My Father Mr Mercédès’, 1961