One hundred & twenty years ago, on the 17th February 1901, a Mercédès car first entered a motor race – at Pau, France. 18 days prior – in Remagen, Germany – was born the man most synonymous with the racing Mercedes-Benz. One of the truly great drivers of the 20th century. Otto Wilhelm Rudolf Caracciola. Rudi Caracciola. “Caratsch”.

3-time European Drivers’ Champion. 3-time European Hillclimb Champion. 6-time winner of the German Grand Prix. The first of only two non-Italian winners of the true Mille Miglia. Winner of the oldest race in our sport – the RAC Tourist Trophy… and so much more in a career than ran from 1922 to 1952.

How to celebrate such an important man? I thought we could take a look at his ‘breakthrough’ race. So let’s consider the 1926 Grosser Preis von Deutschland, the first German Grand Prix… if you don’t count the 1907 Kaiserpreis.

But first, Rudolf Caracciola.

The fourth child of hotel owners, young Rudi was fascinated with cars & racing. When his father died just after The Great War, all thoughts of university and the family business were set aside. Like for so many of his generation, speed was the future. Few would go as far and as fast as Caracciola.

In 1923, after an apprenticeship at the Fafnir car company in Aachen, Germany – including some racing for the marque – 22-year-old Caracciola moved cross country to Dresden, as Fafnir’s sales rep. In truth, he was ‘on the run’ after a nightclub fight with a Belgian army officer. Nevertheless, Dresden was good to him and he was soon snapped-up by Daimler as a Mercédès salesman & racing driver.

Straight out of the blocks, four wins from eight starts in 1923. In 1924 the debut of an iconic pairing – Caracciola on the supercharged Mercédès – produced fifteen race wins. Five more wins in 1925, and the junior driver was primed & ready to breakthrough with both the racing world and general public.

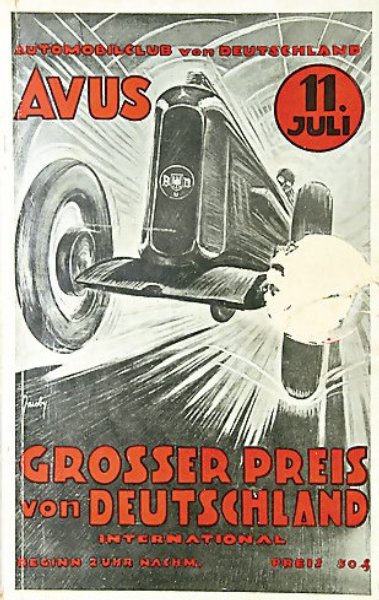

This first Grosser Preis von Deutschland was an odd event, held on a curious circuit. The Berlin ‘Automobil Verkehrs und Übungsstraße’ – AVUS – was part racing track, part testing facility, part prototype autobahn. Little more than a 12-mile stretch of dual carriageway with a hairpin bend at either end, it was less a test of skill than nerve. The 1926 race would require nerves of steel… and unburstable engines.

The 1926 World Championship Grand Prix season was the first for a new 1.5 litre formula… and it had all the impact of a damp squib. Just three cars started the French Grand Prix, and only one was classified at the finish. That was the last thing the Automobilclub von Deutschland needed, so the Grand Prix formula was ignored. In its place, a Formula Libre sportscar race… if you can imagine such a thing.

The fudging of regulations had the desired result, and the AvD received 46 entries. A motley bunch of stripped-down sportscars and barely-disguised ancient & modern Grand Prix & Voiturette machines, supposedly conforming to international sportscar classes D, E & F.

Still, it was the best race entry in Europe that season… as Ferdinando Minoia observed during practice. Minoia would contest the race on a works-entered OM 856. The Officine Meccaniche 856 is a straight-eight, 1.5-litre Grand Prix car – which the AvD placed in sportscar Class F (up to 1500cc)!

While the entry was… eclectic… it wasn’t without its merits. As well as the OM entry, there were five works 1.5-litre supercharged NSU, four works 2.6-litre NAGs, and two 1925 model 1.5 litre Talbot voiturettes – one driven by the great Jean Chassagne. Bugatti, Alfa Romeo, Austro-Daimler, all featured on the start list – but what of Mercédès and our man, Caracciola?

First off – at this point we must stop referring to the team as Mercédès, and start to speak of Mercedes-Benz. The merger of Daimler and Benz having happened on the 28th June 1926.

With an eye to export markets, the works Mercedes-Benz team chose to skip the Berlin race in favour of San Sebastián, in the Spanish Basque Country. There they would compete in a sportscar race – part of a race week which included two international Grands Prix. (A story for another day.)

Of course Mercedes-Benz were keenly aware of the significance of their new home race, and so a plan was hatched… instigated by Caracciola, so he claimed. They reconfigured a pair of their 1924 Monza-type 2-litre, supercharged Grand Prix cars as slightly apologetic ‘sportscars’ and presented them as private entries for Rudi Caracciola and Adolf Rosenberger. The presence of Max Sailer and Ferdinand Porsche in the pit box made it clear that this was no ‘homebrew’ racing effort.

The 1924 Mercédès ‘Monza’ was a neat, purposeful Grand Prix car by Ferdinand Porsche. Its chassis’ reputation was tarnished after the accident that killed Count Zborowski. Its eight-cylinder, supercharged, 2-litre engine – a little ahead of it’s time. It produced a useful 160 PS (158 bhp, “in old money”) but when worked hard it had heat issues. This lead to sparkplug failures, and the car being deemed more suitable for hillclimbs & sprints. Until now. Mercedes-Benz reckoned that the latest plugs were up to the job. AVUS would certainly test them, and Porsche’s engine with it’s “magic power”.

The Mercédès also reportedly – soon to be significantly – carried a small tank of ether, to “aid starting”.

But it was quick! Very fast in fact, as the teams started offical practice for the Grand Prix. Fast, but not unbeatable – the Talbots, Riecken on a HAG and Minioa with his OM all posted fine times too. Good enough to be competitive over 240 miles? Would the Mercédès last?

After the end of official practice on Friday, some of the cars continued to test unofficially. It was then that there was a taste of what was to come.

One of the NAGs joined the track at the South Curve. The riding mechanic signalled, but it was too little… or too late. Gigi Platé was bearing down on them at over 75mph on his Chiribiri. Wheels touch. The Chiribiri flips, slides, and comes to rest… spectators rushing to the scene… pulling the two unconscious men from the machine. Platé is rushed to hospital, severely injured. Carlo Cattaneo – the riding mechanic – dies at the scene. On-board the NAG, driver Wilhelm Heine is severely injured. His riding mechanic, Rolf Richard Kunze, suffers cuts.

And the race meeting continues.

Scrutineering starts at 8am the following morning.

The race, on Sunday. Rain is forecast.

The organisers must have known. How much did the drivers know?

Did they know about AVUS in the wet?

Had they heard about Kurt Neugebauer’s lucky escape a few weeks before?

How, at over 90 mph, the wheels had skipped on the wet track surface. How the NAG racing car had speared to the right. Off the road, into the forest. How it was a miracle that Neugubauer and his mechanic walked away.

The race, on Sunday. Rain is forecast.